Gone Missing: The Town of Snoqualmie Falls

Snoqualmie Valley Historical Museum, Washington

For a year, Fels researched public, private and Weyerhaeuser archives for images and information about the company mill town of Snoqualmie Falls, which had existed for 50 years in the Cascade foothills of Washington State. The popular (and academic) reading of such towns was that they functioned around a core of burly Scandinavian men. Fels' findings suggested otherwise; he produced an exhibition around that point of view for the Snoqualmie Historical Museum, with support from the museum, 4Culture, Washington Humanities, the Simpson Center for the Humanities at the University of Washington, and Arcade. The following is adapted from text in the exhibition:

In 1917, the Snoqualmie Falls Lumber Company began building houses for loggers and mill workers in Snoqualmie, WA. When complete a few years later as a Weyerhaeuser operation, 250 houses, a community hall, schools, ball fields, a Post Office, company store, barbershop, hospital, Japanese bunkhouse, hotel, and a railroad depot comprised the town of Snoqualmie Falls. The town was entirely sustainable, people walked to all essential services; electricity for the town was supplied at very low cost by burning scrap wood in the mill. Weyerhaeuser called the town a 'permanent settlement'. The town was sustainable- but it was not sustained.

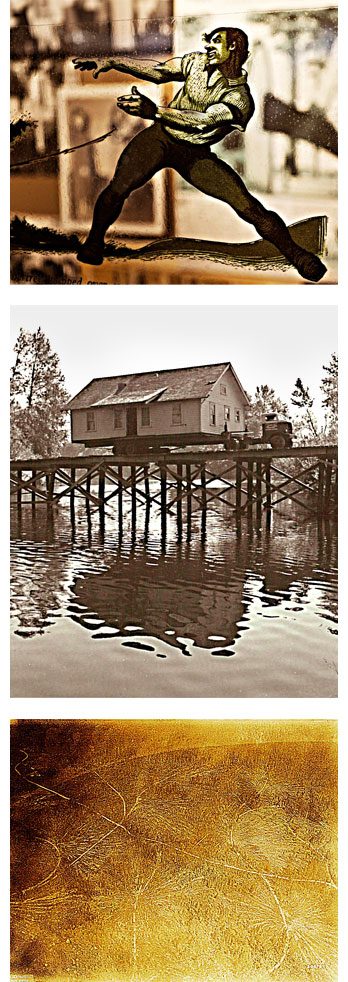

Fifty years ago, the company sold the houses to the renting workers for hauling away. The other structures were pulled down and the town completely disappeared. Hailed by the company as a 'planned community' and a 'social experiment', the site is now covered by a Douglas fir plantation. This is the same 'crop' that the mill once turned into the first nationally branded lumber. Beginning in the 1920s, the lumber was marketed as coming from an especially enlightened and progressive place, and was of course used to construct all the town's houses and structures.

The town's declared purpose was to make it a 'stable' and 'comfortable' base for previously mostly itinerant and 'wild' loggers and mill-hands. From the beginning the success of the initiative was largely dependent on attracting women as the town's civilizing agents. A man employed at the Snoqualmie Falls Lumber Company was entitled to a company house only if he had a wife with whom to occupy it. How and why did a timber company go about carving a town out of the old growth forest where women would want to live? And how did that same focus also serve to keep 'labor troubles' away? The town was founded at the very time that membership in the Wobblies, the International Workers of the World, was near its peak. The growth of the Wobblies seriously threatened to disrupt the supply of timber from NW logging operations.

With the start of World War I came a serious manpower shortage. Large numbers of able-bodied American men were either conscripted or volunteering for the armed forces. In order to open the mill in 1917 (spruce from the mill was needed to construct airplanes, crucial for the war effort), the company arranged with a Japanese contractor who supplied Japanese-born workers. With this core group, along with a few women workers, the mill opened on schedule. According to company records, until 1942 when the Japanese were all exiled to Idaho for internment, they represented half the workers employed at any time. Yet photographs of the mill rarely show them. Nevertheless, the Japanese workers were known to the company as 'well-behaved' and 'hardworkers'. They never caused labor troubles, the very qualities that Weyerhaeuser was trying to inculcate in its workforce by building and maintaining the town. The Japanese and women were the company's stealth weapon for combating the Wobblies.

In its literature about the town Weyerhaeuser wrote that the town's families "enjoyed all the comforts of the city home with the additional advantages of fresh air and plenty of room." The 'tree-growing company' effectively became the 'family growing company'. But by the 1950s radical labor unions were no longer a threat, and TV brought the town-dwellers into a much wider world. Most had automobiles and didn't need to live within watlasng distance of their work. Despite the town being 'permanent', the timber supply was not (and company correspondence shows that it was predicted to last 40 years). By the 1950s all the easily accessible timber had been cut.

Weyerhaeuser emptied out the town of Snoqualmie Falls, but decades later it created another planned community very nearby. The two communities tell us much about the times in which they were built and the different role of women in each. The company is now filing to become a Real Estate Investment Trust. Weyerhaeuser's main crop will soon be houses and planned communities. Even though it has vanished, the town of Snoqualmie Falls was far ahead of its time.